Introduction

Before the advent of photography in America in the 1840s, we must rely on travel narratives, diaries, official records, and personal letters to form a vision of what towns such as Frankfort looked like during their early years. For example, Elias Pym Fordham, a young English immigrant passing through the capital on his way west in 1818, described it as “a smart little town” on the Kentucky River. Arriving on a Sunday in January, he noted “a few smartly dressed young men” picking their way through the “half frozen mud in the street.” Though the Frankfort he saw “was hid in a mud hole,” it had “fine commanding situations around it,” with “smart houses, pleasantly situated,” that looked like “the places of Summer retreat, which the Citizens of London indulge themselves on Sundays.” He observed that Main Street was being paved “in a way that would make a London Paviour laugh.” As for the river, crossed by “a wooden bridge supported by four stone piers,” it “pours a noble stream over a bed of Limestone,”– then as now.

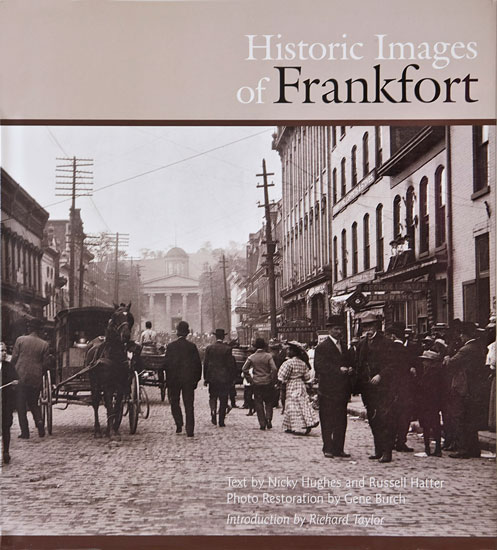

Words carry us only so far. For actual views of Frankfort during this early period we have only a few primitive sketches and an occasional painting, such as the fine watercolor recently acquired by the History Center, painted by a British officer imprisoned in Frankfort during the War of 1812. Looking west toward the river, it shows an expanse of North Frankfort that we would never know without it — just as many images in this book do for us today, mixing the familiar with the vanished, introducing us to individuals identified or unknown whose descendants still walk the streets of Frankfort and whose family names are often found in the local phonebook.

Acting on a suggestion of Tony Charters, Frankfort’s former Director of Tourism, a group of us met on February 13, 2003, to discuss a project for publishing a collection of old photographs of Frankfort. The group included Russ Hatter, Nicky Hughes, Dr. Gene Burch, Jeff Jeffers, and Bill Rodgers. Meeting before work every couple of weeks at the office of Frankfort’s curator of historic sites on West Broadway, we gradually hammered out a plan to compile and publish a book of images depicting Frankfort’s past. Early on, we decided to be very selective in the images included, using only those of high quality that embodied noteworthy or representative facets of Frankfort and Franklin County during the past two centuries. Choices were hard because we discovered that we had enough photos for several books. Those that we did not present in this book would be archived for use by others as a resource for historical and genealogical research, for use in future books, or simply preserved as a means to satisfy those curious about how Frankfort and outlying communities appeared in the past. The book was not to be an illustrated history because there were too many gaps, too much hit-and-miss in the visual record to be comprehensive. It was not to be a gallery of famous Frankfortians because likenesses of these persons were familiar to most readers through other publications. Instead, it would focus on capturing the life of Frankfort — its citizens working and playing, coping with floods and fires, celebrating special events, relaxing with friends and family, boating on the Kentucky River, courting and congregating, selling and consuming. It would be in part a record of the built environment, much of which has been altered or disappeared altogether as Frankfort evolved from a rural capital to a bustling seat of commerce and state government. In lieu of following a strict chronology, we divided the photographs into categories that became sections of the book. Since many of the available photographs had been printed in earlier histories, the committee agreed that we should seek new images, asking members of the Frankfort community to rifle their attics and family albums for unpublished views of the city and its citizens that depicted a Frankfort few of us had seen.